Extending the Life of Legacy Fabs

Extending the Life of Legacy Fabs….

The demands on semiconductor manufacturing have never been higher. From the surge in AI hardware to the relentless pace of automotive electronics and consumer devices, production capacity is being stretched in every direction. While the most advanced fabs operate with the latest process tools and government incentives, many facilities are tasked with doing more using equipment installed decades ago. These legacy fabs face tighter margins, fewer subsidies, and limited pricing leverage, making every hour of uptime a matter of survival.

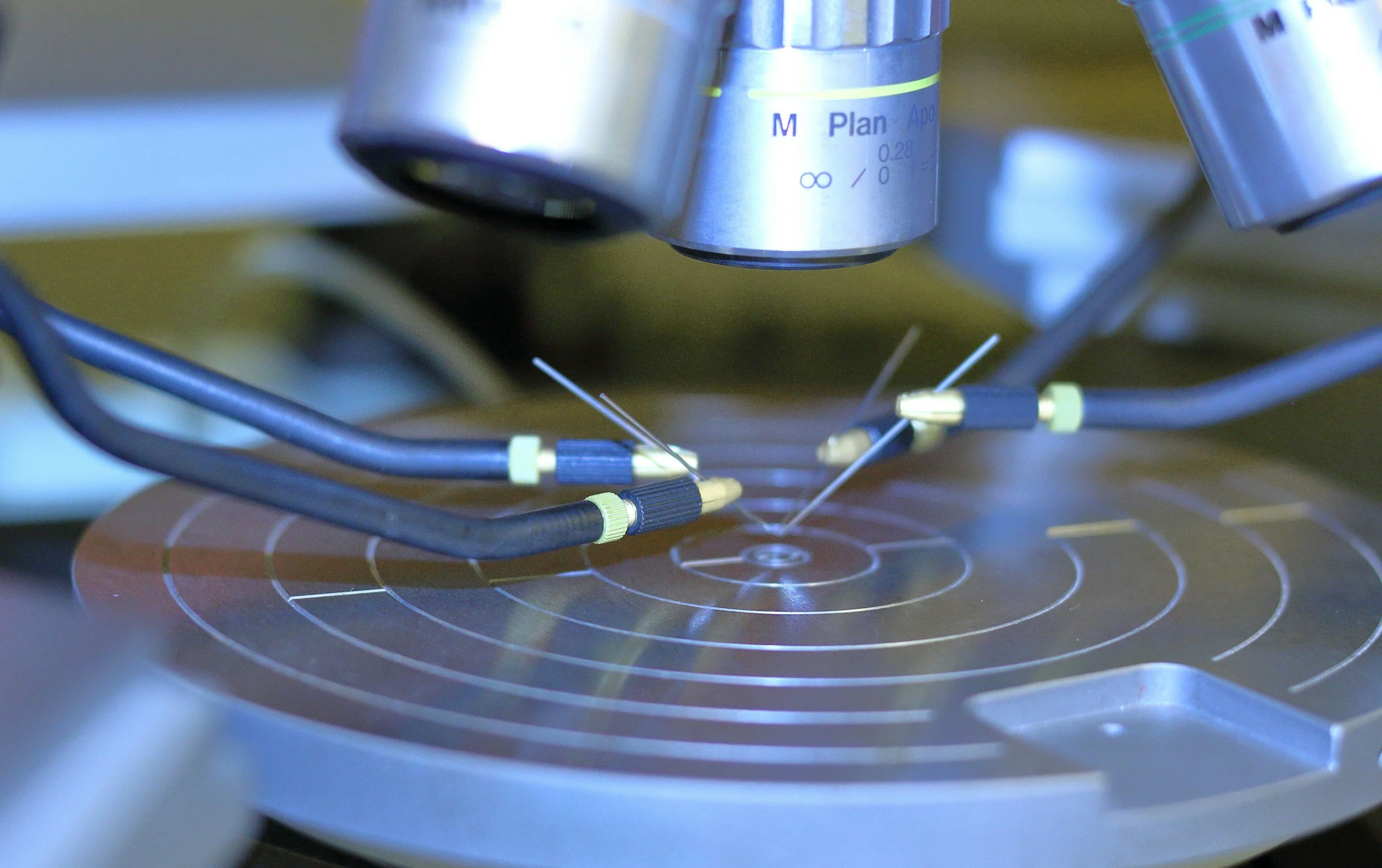

Among the many moving parts that keep a fab operational, pendulum valves rarely draw attention outside maintenance circles. Yet these specialized vacuum valves are pivotal to wafer processing. Installed between process chambers and vacuum pumps in etch and deposition equipment, they control gas flow with a swinging seal plate, the pendulum action that opens and closes against the sealing surface. In an ultra-high-vacuum environment laced with corrosive gases, the integrity of that seal is everything.

A valve that works as intended keeps pressure stable, the process clean, and yields intact. A valve that fails can bring a tool worth millions to an abrupt stop. Production queues collapse, and wafers already in the chamber may be contaminated or damaged. In severe cases, the loss from a single run can run into hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Where the real cost lies

Looking at the total cost of ownership (TCO) for pendulum valves, the numbers tell their own story. Unplanned downtime is by far the most significant expense, often accounting for 60 to 80 per cent of lifetime cost. Maintenance comes next, consuming 15 to 30 per cent, and capital replacement is the smallest category, rarely more than 15 per cent.

The stark reality is that the component cost, a valve in the tens of thousands or a seal for a few hundred, pales beside the hit from even a short outage. One stalled process step can disrupt upstream and downstream operations, bottlenecking the whole production line. And in older fabs, getting the tool back online can take far longer than in a state-of-the-art facility.

The availability of parts is a critical factor. Newer fabs typically hold essential spares on site or can have them shipped overnight from the manufacturer. For legacy tools, the story is very different. OEM parts may have been discontinued years ago. Replacement components often must be sourced from refurbishers or third-party suppliers, and lead times can stretch from days to weeks. Every extra hour of delay is another line item on the loss sheet.

Why do older plants carry more risk

Technology has evolved not just in scale but in the way valves are designed and protected. Modern units use seal materials and surface coatings engineered to withstand harsher chemistries for longer periods. Etch and deposition gases themselves have been refined to reduce corrosiveness.

Legacy fabs do not always have these advantages. Many still run chlorine-rich or CFC-based gases that are far more aggressive. Seal specifications are often decades old reflecting material choices that can’t withstand today’s extreme conditions and are prone to hardening, cracking, or pitting under attack. Coatings, if present at all, are less sophisticated and more prone to wear. The result is a higher likelihood of leaks, particle generation, and premature failure.

Another vulnerability is tool redundancy. Cutting-edge fabs often have large numbers of identical tools capable of running the same process recipe, so wafers can be redirected if one tool fails. Legacy fabs might have just one qualified tool for a given process step. If that goes offline, there is nowhere else for the wafers to go. Idle work-in-progress can quickly exceed safe process windows, forcing rework or scrapping of valuable product.

Project News